By its very nature, our recent photozine Perdu sur le vaisseau spatial (Lost on the Spaceship), by Jean-Paul Marsaud, has been shrouded in a little mystery.

By its very nature, our recent photozine Perdu sur le vaisseau spatial (Lost on the Spaceship), by Jean-Paul Marsaud, has been shrouded in a little mystery.

However, in this brief essay (which will come with Perdu as a supplement), Colossive’s “Tom Murphy” looks back at the unlikely-sounding genesis of the project.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

A couple of weeks after moving from Chorley to London in 1986, I saw Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville at the Barbican. Which was exciting enough for a wide-eyed nipper with a Billy the Fish football perm who’d just hopped off the National Express 570 Rapide.

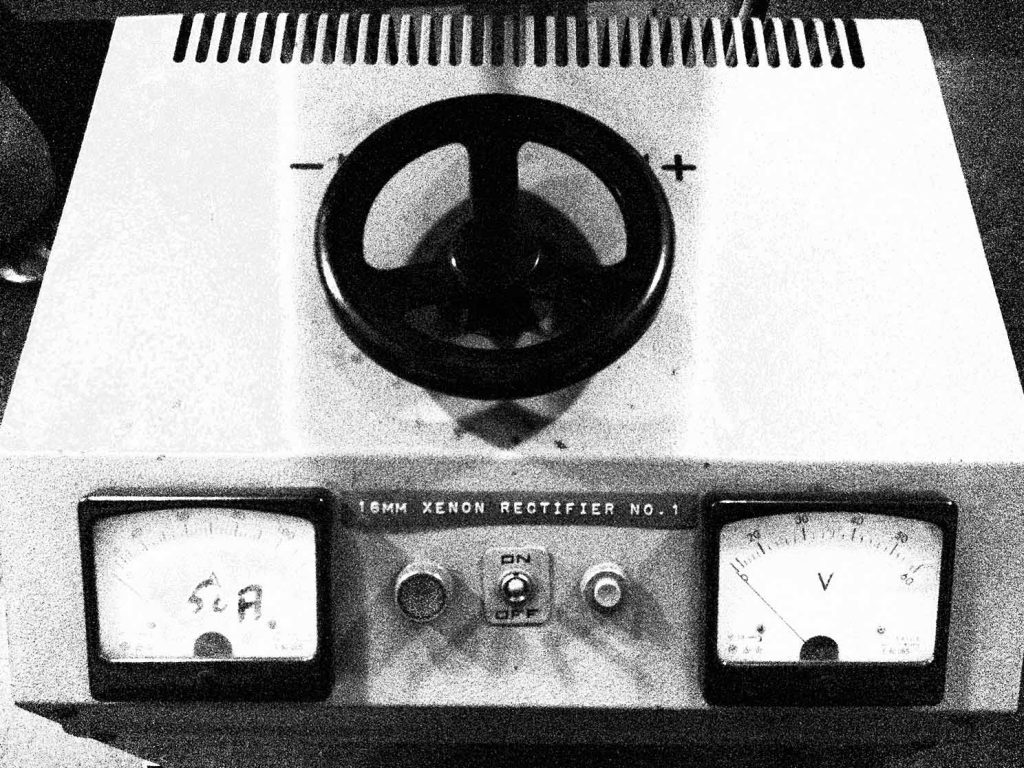

However, the main feature was preceded by a cryptic yet compelling 16mm short called Mitte, by a compatriot of Godard’s named Jean-Paul Marsaud. Later, with a more functional critical vocabulary at my fingertips, I’d be able to wax lyrical about Mitte. However, at the time its mesmerising sequences depicting a glide through an unidentified city became a formative experience that I struggled to put into words and which had a profound effect on how I perceived my new metropolitan environment.

A bit of (pre-internet) research revealed that while Marsaud had taken pains to remain generally under the radar, he had made two more similar films – Proxima and Espacio – that also seemed to beguile as much as they baffled. A huddle of cognoscenti would gather at festival screenings and private cinema clubs to pore over these films, in which the strata of urban reality unfolded like a thousand-petalled lotus bloom.

A bit of (pre-internet) research revealed that while Marsaud had taken pains to remain generally under the radar, he had made two more similar films – Proxima and Espacio – that also seemed to beguile as much as they baffled. A huddle of cognoscenti would gather at festival screenings and private cinema clubs to pore over these films, in which the strata of urban reality unfolded like a thousand-petalled lotus bloom.

Then, in 1992, le cataclysme. At a time of great personal distress, Marsaud destroyed the negatives and prints of his three films and withdrew from public life. Despite persistent rumours, it seemed that the films didn’t even live on as an n‑th generation VHS.

And that might have been the end of the story, had it not been for a chance encounter at London’s Institut français at which I became an unlikely instrument of destiny.

Attending a bande desinée (comics) event and making awkward smalltalk with a couple of acquaintances, I became aware of a similarly uncomfortable looking man on the periphery of the group. Later, in the pub, one of my rosbif companions revealed that the man, known only as Jean-Paul, was nicknamed le fantôme (the ghost) around London’s French community, and that he had apparently been a great artist who had suffered a breakdown and destroyed his life’s work.

Attending a bande desinée (comics) event and making awkward smalltalk with a couple of acquaintances, I became aware of a similarly uncomfortable looking man on the periphery of the group. Later, in the pub, one of my rosbif companions revealed that the man, known only as Jean-Paul, was nicknamed le fantôme (the ghost) around London’s French community, and that he had apparently been a great artist who had suffered a breakdown and destroyed his life’s work.

With my mind making connections and my curiosity piqued, I returned to the Institut français and pestered the librarian, who reluctantly confirmed Jean-Paul’s identity and agreed to pass my details to ‘the ghost’. Weeks passed, and, as I’d expected, no contact was forthcoming. Unable to let go, I made increasingly regular visits to the French enclave of South Kensington, wondering if I’d ever track down my elusive quarry – or even if, true to his nickname, he was a phantom who had once more dissolved into incorporeality.

I had all but given up hope when fate again intervened. Having dived into an unpromising chain pub for an early-afternoon loosener, I heard a familiar voice order a crème de cassis from the other side of the frosted-glass snob screen.

I had all but given up hope when fate again intervened. Having dived into an unpromising chain pub for an early-afternoon loosener, I heard a familiar voice order a crème de cassis from the other side of the frosted-glass snob screen.

Using my stool as a prop to lever myself upwards, I peered over the screen to see none other than the auteur manqué Marsaud, peering intently into the maroon depths of his drink as if seeking the likeness of a long-dead lover.

As I introduced myself, my bumbling – and uncharacteristic – enthusiasm seemed to drive him further into his retreat. However, a crack appeared in the curtain when he waspishly corrected me over my apparent misinterpretation of one of his films. With the regular replenishment of his glass, he began to defrost (albeit never showing the slightest bit of interest in my own life or work).

I probed him gently on the destruction of his films, and in a startling moment he revealed that he’d kept an archive of sketches and photographs from the production of his films. With a certitude that I generally lack in my quotidian routine, I resolved not to let le fantôme dematerialise until he had agreed to the Colossive Gallery staging an exhibition of these priceless artefacts. As the sun crept lower and the bar bill did very much the opposite, a deal of sorts was reached.

Many terse episodes of psychodrama were still to be played out over that summer and autumn, but on October 15th the Colossive Gallery opened ‘All That Remains – The Lost Films of JP Marsaud’. But you know that already, don’t you? You were probably there.

Anyway, the show went – as they say – like gangbusters (despite JP failing to grace us with his presence even once). When the fortnight was up I met JP as arranged – back at the Institut français – to return his material. I’d anticipated that he’d be late, but when he slouched in, in his usual laboured gait, I was intrigued to see another package under his arm. Without a greeting he dropped a foxed envelope, emblazoned with coffee rings, on the table in front of me. With the most minimal of gestures, he indicated that I should look within.

Anyway, the show went – as they say – like gangbusters (despite JP failing to grace us with his presence even once). When the fortnight was up I met JP as arranged – back at the Institut français – to return his material. I’d anticipated that he’d be late, but when he slouched in, in his usual laboured gait, I was intrigued to see another package under his arm. Without a greeting he dropped a foxed envelope, emblazoned with coffee rings, on the table in front of me. With the most minimal of gestures, he indicated that I should look within.

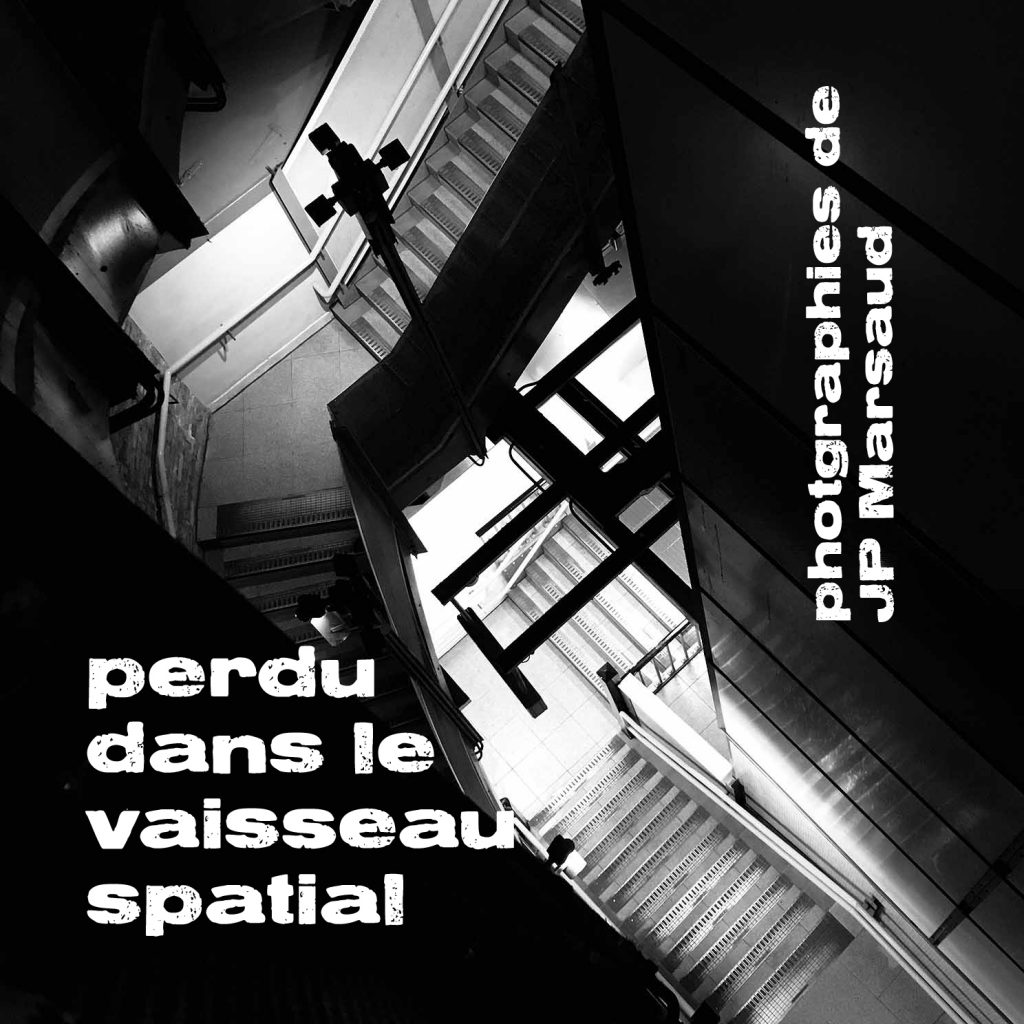

What I found was a disordered series of black-and-white photographs of various claustrophobic, even sepulchural locations. He wouldn’t be drawn on their origin or purpose, but wanted my opinion as to whether any money could be made from them. Over a coffee (and a seemingly obligatory Cognac) we reached what could loosely be termed an agreement to publish them as a zine. He didn’t bother to hide his disappointment – his disdain, even – when I revealed the scale of production and promotion that Colossive would be able to provide. However, pouring another Cognac on the troubled waters seemed to do the job.

However, my request for a title for the work seemed to test his forbearance to destruction. Downing his drink (after a reflexive swill round the glass), he rose with a previously unsuggested nimbleness and rolled back out into the London rain.

However, my request for a title for the work seemed to test his forbearance to destruction. Downing his drink (after a reflexive swill round the glass), he rose with a previously unsuggested nimbleness and rolled back out into the London rain.

A couple of mornings later, a seemingly hand-delivered postcard was waiting in the gallery letter box, bearing nothing but the words Perdu sur le vaisseau spatial. Lost on the spaceship. So that’s what it is.

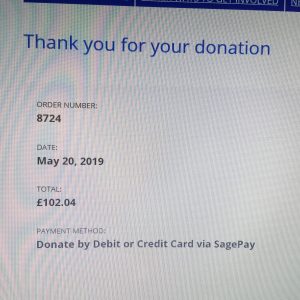

After our triumphant debut at last year’s

After our triumphant debut at last year’s